Մասնակից:Manedarbinyan/Ավազարկղ

Հերոս (իգական՝ հերոսուհի) իրական անձ կամ պրոտագոնիստ, ով, առերեսվելով վտանգի, պայքարում է դրա դեմ հնարամտությամբ, խիզախությամբ և քաջությամբ։ Դասական դյուցազներգության մեջ հերոսի նախատիպը այդ ամենն անում էր հանուն փառքի ու պատվի։ Հետդասական և ժամանակակից հերոսները, մյուս կողմից, սխրագործություններ են կատարում կամ անձնազոհություն են ցուցաբերում ընդհանուր բարիքի համար, այլ ոչ թե հարստության, հպարտության և հռչակի նպատակով։ Հերոսի հականիշը չարագործն է[1]։ Հերոս բառի հետ կապված այլ տերմինները կարող են ներառել նաև լավ մարդկանց։

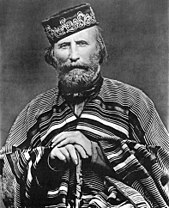

Դասական գրականության մեջ հերոսը էպոսի գլխավոր կերպարն է, որը հայտնի է դարձել ժողովրդական լեգենդներից[2]։ Ժամանակի ընթացքում փոխվել է հերոսի սահմանումը։ Մերիամ Ուեբսթերի բառարանում հերոսը բացատրվում է որպես «մարդ, ում սիրում են մեծ ու խիզախ գործերի կամ լավ որակների համար»[3]։ Դիցաբանական հերոսներից են Գիլգամեշը, Աքիլլեսը և Իփիգենիան, պատմական և ժամանակակից հերոսներից՝ Ժաննա դ'Արկը, Ջուզեպպե Գարիբալդին, Սոֆի Շոլը, Էլվին Յորքը, Օդի Մերֆին և Չառլզ Յեգերը, և սուպերհերոսներից՝ Սուպերմենը, Սարդ-Մարդը, Բեթմենը և Կապիտան Ամերիկան։

Ստուգաբանություն

խմբագրելՀերոս բառը ծագում է հունարեն ἥρως (հերոս) բառից, «հերոսը» (բառացի «պաշտպան»),[4] հատկապես այնպիսի մեկն է, ինչպիսին Հերակլեսը, որն ունի աստվածային ծագում կամ ավելի ուշ տրված աստվածային արժեքներ[5]։ Նախքան «Linear B»-ի վերծանումը, բառի սկզբնական ձևը *ἥρωϝ-, hērōw- էր, սակայն Միկենյան բաղադրյալը՝ ti-ri-se-ro-e ցույց է տալիս -w- տառի բացակայությունը։ Հերոն, որպես անուն, հանդիպում է նախահոմերոսյան հունական դիցաբանությունում, որտեղ Հերոն Աֆրոդիտե աստվածուհու քրմուհին էր։

Ըստ «The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language»-ի, հնդեվրոպական նախալեզվում արմատը *ser-ն է, որը նշանակում է «պաշտպանել»։ Ըստ Էրիկ Փարթրիջի «Origins»-ի հունարեն «hērōs» բառը «նման է» լատիներեն seruāre-ին, որը նշանակում է պաշտպանել։ Փարթրիջը եզրակացնում է․ «Հերա և հերոս բառերի հիմնական իմաստը «պաշտպան»-ն է»։ Ռոբերտ Բեքեսը մերժում է բառի հնդեվրոպական ծագումը և պնդում է, որ բառն ունի նախահունական սկզբնաղբյուր[6]։ Հերան հունական դիզաբանության աստվածուհի էր՝ բազում հատկություններով, ներառյալ պաշտպանությունը, և նրա պաշտամունքը, ըստ երևույթին, ունի նմանատիպ հնդեվրոպական սկզբնաղբյուր։

Հին ժամանակներ

խմբագրելԴասական հերոսը համարվում է «ռազմիկ, ով ապրում և մահանում է պատվի համար» և հասնում է փառքի «այն խելքի և զորության շնորհիվ, որով նա սպանում է»[7]։ Յուրաքանչյուր դասական հերոսի կյանքը կենտրոնացած է մարտի վրա, որը տեղի է ունենում պատերազմի կամ էպիկական որոնումների ժամանակ։ Դասական հերոսները հիմնականում կիսաստվածային են և արտասովոր շնորհալի, ինչպիսին Աքիլլեսն է, և նրանք հերոս են դառնում վտանգավոր հանգամանքներում[2]։ Չնայած այս հերոսները աներևակայելի հնարամիտ և ճարպիկ են, նրանք հաճախ նաև անխոհեմ են, վտանգում են իրենց համախոհների կյանքը չնչին հարցերի պատճառով, և երեխայի նման դրսևորում են գոռոզ վարքագիծ[2]։ Դասական ժամանակաշրջանում մարդիկ հերոսների հանդեպ տածում էին մեծ հարգանք և մեծ նշանակություն էին տալիս նրանց, այդ ամենը էպոսներում ներկայացնելով[8]։ Այս մահկանացուների գոյությունը շրջադարձային էր ժողովրդի և գրողների համար, քանի որ աստվածներից դարձել էին մահկանացուներ, որոնց փառքի հերոսական պահերը հիշվում են հետնորդների կողմից[2]։

Հեկտորը Տրոյայի արքայազնն էր և Տրոյական պատերազմի լավագույն ռազմիկը, ով հիմնականում հայտնի է Հոմերոսի «Իլիական» վիպերգից։ Հեկտորը դարձավ տրոյացիների ղեկավարը և Տրոյայի պաշտպանության գործում նրանց աջակիցը՝ «սպանելով 31,000 հույն զինվորի»՝ ըստ Հիջայնուսի[9]։ Հեկտորը հայտնի էր ոչ միայն իր քաջությամբ, այլև իր ազնիվ և քաղաքակիրթ բնավորությամբ։ Հոմերոսը նրան նկարագրում է որպես խաղաղասեր, խելամիտ, ինչպես նաև համարձակ, լավ որդու, հոր և ամուսնու, առանց որևէ գաղտնի շարժառիթի։ Այնուամենայնիվ, նրա ընտանեկան արժեքները մեծապես հակասում են «Իլիականում» նրա հերոսական ձգտումներին, քանի որ նա չի կարող լինել և՛ Տրոյայի պաշտպանը, և՛ հայր իր երեխայի համար[7]։ Հեկտորը, ի վերջո, դավաճանվում է աստվածների կողմից, երբ Աթենասը հայտնվում է ծպտված որպես իր դաշնակից Դեյֆոբուսը և համոզում նրան մարտահրավեր նետել Աքիլլեսին, ով էլ սպանում է նրան[10]։

Աքիլլեսը հույն հերոս է, ով համարվում էր Տրոյական պատերազմի ամենաանհարկու ռազմիկը և «Իլիական»-ի գլխավոր հերոսը։ Նա կիսաստված էր՝ Թետիսի և Պելևսի որդին։ Նա գերմարդկային ուժ էր ցուցաբերում մարտի դաշտում և աստվածների հետ սերտ հարաբերությունների մեջ էր: Աքիլլեսը, ինչպես հայտնի է, հրաժարվեց կռվել Ագամեմնոնի կողմից իր անարգանքից հետո, և պատերազմ վերադարձավ միայն զայրույթից դրդված, քանի որ Հեկտորն սպանել էր իր մանկության ընկերոջը՝ Պատրոկլեսին[10]։ Աքիլլեսը հայտնի էր իր անկառավարելի զայրույթով, ինչն էլ բնորոշում էր նրա արյունարբու արարքներից շատերը, ինչպես օրինակ՝ Հեկտորի դիակը Տրոյա քաղաքով մեկ քարշ տալով պղծելը։ Աքիլլեսը ողբերգական դեր է խաղում «Իլիական»-ում, որն առաջացել է էպոսի մշտական ապամարդկայնացման հետևանքով, որտեղ նրա menis-ը (ցասում) հաղթում է philos-ին (սերը)[7]։

Դիցաբանության հերոսները հաճախ ունենում են մտերիմ, սակայն կոնֆլիկտային հարաբերություններ աստվածների հետ։ Օրինակ՝ Հերակլեսի անունը նշանակում է Հերայի փառքը, մինչդեռ նրան ամբողջ կյանքում ամբողջ տանջել է Հերան՝ հույն աստվածների դիցուհին։ Սակայն ամենազարմանալի օրինակը աթենյան թագավոր Իրեխտյուսն է, ում Պոսեյդոնն սպանել է Աթենասին քաղաքի հովանավոր աստված ընտրելու համար։ Երբ աթենացիները Ակրոպոլիսում երկրպագում էին Իրեխտյուսին, նրանք նրան անվանում էին Պոսեյդոն Իրեխտյուս:

Դասական հերոսների պատմություներում մեծ դեր է կատարում ճակատագիրը։ Դասական հերոսները նշանավորվում էին ի սկզբանե վտանգավոր մարտական նվաճումներով[7]։ Հունական դիցաբանության աստվածները, հաղորդակցվելով հերոսների հետ, հաճախ կանխագուշակում էին մարտում նրանց հավանական մահը։ Անթիվ-անհամար հերոսներ և աստվածներ մեծ ջանքեր են գործադրում՝ փոխելու իրենց կանխորոշված ճակատագրերը, բայց առանց հաջողության, քանի որ ոչ մեկը, ոչ մարդն ու անմահը չեն կարող փոխել իրենց ճակատագիրը[11]։ Սրա ամենաբնորոշ օրինակն է «Էդիպուս արքան»։ Թեբեի Լայուս արքան, պարզելով, որ իր որդին՝ Էդիպը իրեն սպանելու է, հեռացնում է նրան թագավորությունից՝ ձեռնարկելով որդուն մահը։ Երբ Էդիպը շատ տարիներ անց ճանապարհին հանդիպում է իր հորը, որը չէր ճանաչում որդուն, սպանում է նրան առանց մտածելու: Ճանաչվածության բացակայությունը Էդիպուսին հնարավորություն տվեց սպանել իր հորը՝ հեգնանքով ավելի կապելով հորը իր ճակատագրին[11]։

Հերոսական պատմությունները կարող են նաև բարոյական օրինակ ծառայել։ Այնուամենայնիվ, դասական հերոսները հաճախ չէին մարմնավորում ազնիվ, կատարյալ բարոյական հերոսի քրիստոնեական գաղափարը[12]։ Օրինակ՝ Աքիլլեսի ցասումը հանգեցնում էր անողոք կոտորածի, իսկ նրա ճնշող հպարտությունը հանգեցնում է նրան, որ նա միայն միանում է Տրոյական պատերազմին, քանի որ նա չէր ցանկանում, որ իր զինվորները նվաճեին ողջ փառքը: Դասական հերոսները, անկախ նրանց բարոյականությունից, դարձան կրոնական: Անտիկ աշխարհում պաշտամունքները, որոնք երկրպագում էին աստվածացված հերոսներին, ինչպիսիք են՝ Հերակլեսը, Պերսևսը և Աքիլլեսը, կարևոր դեր են խաղացել հին հունական կրոնում[13]։ Հին Հունաստանում հերոսների պաշտամունքը երկրպագում էր բանավոր էպիկական ցիկլի հերոսներին, ընդ որում այս հերոսները հաճախ օրհնում էին, հատկապես բուժվողներին[13]։

Դիցաբանություն և միաբանություն

խմբագրելThe concept of the "Mythic Hero Archetype" was first developed by Lord Raglan in his 1936 book, The Hero, A Study in Tradition, Myth and Drama. It is a set of 22 common traits that he said were shared by many heroes in various cultures, myths, and religions throughout history and worldwide. Raglan argued that the higher the score, the more likely the figure is mythical.[14]

The concept of a story archetype of the standard monomythical "hero's quest" that was reputed to be pervasive across all cultures is somewhat controversial. Expounded mainly by Joseph Campbell in his 1949 work The Hero with a Thousand Faces, it illustrates several uniting themes of hero stories that hold similar ideas of what a hero represents despite vastly different cultures and beliefs. The monomyth or Hero's Journey consists of three separate stages: the Departure, Initiation, and Return. Within these stages, there are several archetypes that the hero of either gender may follow, including the call to adventure (which they may initially refuse), supernatural aid, proceeding down a road of trials, achieving a realization about themselves (or an apotheosis), and attaining the freedom to live through their quest or journey. Campbell offered examples of stories with similar themes, such as Krishna, Buddha, Apollonius of Tyana, and Jesus.[15] One of the themes he explores is the androgynous hero, who combines male and female traits, such as Bodhisattva: "The first wonder to be noted here is the androgynous character of the Bodhisattva: masculine Avalokiteshvara, feminine Kwan Yin."[15] In his 1968 book, The Masks of God: Occidental Mythology, Campbell writes, "It is clear that, whether accurate or not as to biographical detail, the moving legend of the Crucified and Risen Christ was fit to bring a new warmth, immediacy, and humanity, to the old motifs of the beloved Tammuz, Adonis, and Osiris cycles."[16]

Սլավոնական հեքիաթներ

խմբագրելVladimir Propp, in his analysis of Russian fairy tales, concluded that a fairy tale had only eight dramatis personæ, of which one was the hero,[17] and his analysis has been widely applied to non-Russian folklore. The actions that fall into such a hero's sphere include:

- Departure on a quest

- Reacting to the test of a donor

- Marrying a princess (or similar figure)

Propp distinguished between seekers and victim-heroes. A villain could initiate the issue by kidnapping the hero or driving him out; these were victim-heroes. On the other hand, an antagonist could rob the hero, or kidnap someone close to him, or, without the villain's intervention, the hero could realize that he lacked something and set out to find it; these heroes are seekers. Victims may appear in tales with seeker heroes, but the tale does not follow them both.[17]

Պատմական ուսումնասիրություններ

խմբագրելThe philosopher Hegel gave a central role to the "hero", personalized by Napoleon, as the incarnation of a particular culture's Volksgeist and thus of the general Zeitgeist. Thomas Carlyle's 1841 work, On Heroes, Hero-Worship, & the Heroic in History, also accorded an essential function to heroes and great men in history. Carlyle centered history on the biographies of individuals, as in Oliver Cromwell's Letters and Speeches and History of Frederick the Great. His heroes were not only political and military figures, the founders or topplers of states, but also religious figures, poets, authors, and captains of industry.

Explicit defenses of Carlyle's position were rare in the second part of the 20th century. Most in the philosophy of history school contend that the motive forces in history may best be described only with a wider lens than the one that Carlyle used for his portraits. For example, Karl Marx argued that history was determined by the massive social forces at play in "class struggles", not by the individuals by whom these forces are played out. After Marx, Herbert Spencer wrote at the end of the 19th century: "You must admit that the genesis of the great man depends on the long series of complex influences which has produced the race in which he appears, and the social state into which that race has slowly grown...[b]efore he can remake his society, his society must make him."[21] Michel Foucault argued in his analysis of societal communication and debate that history was mainly the "science of the sovereign", until its inversion by the "historical and political popular discourse".

Modern examples of the typical hero are, Minnie Vautrin, Norman Bethune, Alan Turing, Raoul Wallenberg, Chiune Sugihara, Martin Luther King Jr., Mother Teresa, Nelson Mandela, Oswaldo Payá, Óscar Elías Biscet, and Aung San Suu Kyi.

The Annales school, led by Lucien Febvre, Marc Bloch, and Fernand Braudel, would contest the exaggeration of the role of individual subjects in history. Indeed, Braudel distinguished various time scales, one accorded to the life of an individual, another accorded to the life of a few human generations, and the last one to civilizations, in which geography, economics, and demography play a role considerably more decisive than that of individual subjects.

Among noticeable events in the studies of the role of the hero and great man in history one should mention Sidney Hook's book (1943) The Hero in History.[24] In the second half of the twentieth century such male-focused theory has been contested, among others by feminists writers such as Judith Fetterley in The Resisting Reader (1977)[25] and literary theorist Nancy K. Miller, The Heroine's Text: Readings in the French and English Novel, 1722–1782.[26]

In the epoch of globalization an individual may change the development of the country and of the whole world, so this gives reasons to some scholars to suggest returning to the problem of the role of the hero in history from the viewpoint of modern historical knowledge and using up-to-date methods of historical analysis.[27]

Within the frameworks of developing counterfactual history, attempts are made to examine some hypothetical scenarios of historical development. The hero attracts much attention because most of those scenarios are based on the suppositions: what would have happened if this or that historical individual had or had not been alive.[28]

Ժամանակակից ֆանտաստիկա

խմբագրելThe word "hero" (or "heroine" in modern times), is sometimes used to describe the protagonist or the romantic interest of a story, a usage which may conflict with the superhuman expectations of heroism.[29] A good example is Anna Karenina, the lead character in the novel of the same title by Leo Tolstoy. In modern literature the hero is more and more a problematic concept. In 1848, for example, William Makepeace Thackeray gave Vanity Fair the subtitle, A Novel without a Hero, and imagined a world in which no sympathetic character was to be found.[30] Vanity Fair is a satirical representation of the absence of truly moral heroes in the modern world.[31] The story focuses on the characters, Emmy Sedley and Becky Sharpe (the latter as the clearly defined anti-hero), with the plot focused on the eventual marriage of these two characters to rich men, revealing character flaws as the story progresses. Even the most sympathetic characters, such as Captain Dobbin, are susceptible to weakness, as he is often narcissistic and melancholic.

The larger-than-life hero is a more common feature of fantasy (particularly in comic books and epic fantasy) than more realist works.[29] However, these larger-than life figures remain prevalent in society. The superhero genre is a multibillion-dollar industry that includes comic books, movies, toys, and video games. Superheroes usually possess extraordinary talents and powers that no living human could ever possess. The superhero stories often pit a super villain against the hero, with the hero fighting the crime caused by the super villain. Examples of long-running superheroes include Superman, Wonder Woman, Batman, and Spider-Man.

Research indicates that male writers are more likely to make heroines superhuman, whereas female writers tend to make heroines ordinary humans, as well as making their male heroes more powerful than their heroines, possibly due to sex differences in valued traits.[32]

Փիլիսոփայություն

խմբագրելSocial psychology has begun paying attention to heroes and heroism.[33] Zeno Franco and Philip Zimbardo point out differences between heroism and altruism, and they offer evidence that observer perceptions of unjustified risk play a role above and beyond risk type in determining the ascription of heroic status.[34]

Psychologists have also identified the traits of heroes. Elaine Kinsella and her colleagues[35] have identified 12 central traits of heroism, which consist of brave, moral integrity, conviction, courageous, self-sacrifice, protecting, honest, selfless, determined, saves others, inspiring, and helpful. Scott Allison and George Goethals[36] uncovered evidence for "the great eight traits" of heroes consisting of wise, strong, resilient, reliable, charismatic, caring, selfless, and inspiring. These researchers have also identified four primary functions of heroism.[37] Heroes give us wisdom; they enhance us; they provide moral modeling; and they offer protection.

An evolutionary psychology explanation for heroic risk-taking is that it is a costly signal demonstrating the ability of the hero. It may be seen as one form of altruism for which there are several other evolutionary explanations as well.[38][39]

Roma Chatterji has suggested that the hero or more generally protagonist is first and foremost a symbolic representation of the person who is experiencing the story while reading, listening, or watching;[40] thus the relevance of the hero to the individual relies a great deal on how much similarity there is between them and the character. Chatterji suggested that one reason for the hero-as-self interpretation of stories and myths is the human inability to view the world from any perspective but a personal one.

In the Pulitzer Prize-winning book, The Denial of Death, Ernest Becker argues that human civilization is ultimately an elaborate, symbolic defense mechanism against the knowledge of our mortality, which in turn acts as the emotional and intellectual response to our basic survival mechanism. Becker explains that a basic duality in human life exists between the physical world of objects and a symbolic world of human meaning. Thus, since humanity has a dualistic nature consisting of a physical self and a symbolic self, he asserts that humans are able to transcend the dilemma of mortality through heroism, by focusing attention mainly on the symbolic self. This symbolic self-focus takes the form of an individual's "immortality project" (or "causa sui project"), which is essentially a symbolic belief-system that ensures that one is believed superior to physical reality. By successfully living under the terms of the immortality project, people feel they can become heroic and, henceforth, part of something eternal; something that will never die as compared to their physical body. This he asserts, in turn, gives people the feeling that their lives have meaning, a purpose, and are significant in the grand scheme of things. Another theme running throughout the book is that humanity's traditional "hero-systems", such as religion, are no longer convincing in the age of reason. Science attempts to serve as an immortality project, something that Becker believes it can never do, because it is unable to provide agreeable, absolute meanings to human life. The book states that we need new convincing "illusions" that enable people to feel heroic in ways that are agreeable. Becker, however, does not provide any definitive answer, mainly because he believes that there is no perfect solution. Instead, he hopes that gradual realization of humanity's innate motivations, namely death, may help to bring about a better world. Terror Management Theory (TMT) has generated evidence supporting this perspective.

Մտավոր և ֆիզիկական ինտեգրում

խմբագրելExamining the success of resistance fighters on Crete during the Nazi occupation in WWII, author and endurance researcher C. McDougall drew connections to the Ancient Greek heroes and a culture of integrated physical self-mastery, training, and mental conditioning that fostered confidence to take action, and made it possible for individuals to accomplish feats of great prowess, even under the harshest of conditions. The skills established an "...ability to unleash tremendous resources of strength, endurance, and agility that many people don't realize they already have."[41] McDougall cites examples of heroic acts, including a scholium to Pindar's Fifth Nemean Ode: "Much weaker in strength than the Minotaur, Theseus fought with it and won using pankration, as he had no knife." Pankration is an ancient Greek term meaning "total power and knowledge," one "...associated with gods and heroes...who conquer by tapping every talent."[42]

Տես նաև

խմբագրել- Մարտաֆիլմի հերոս

- Հակահերոս

- Բայրոնյան հերոս

- Կարնեգիի հերոսների հիմնադրամ

- Մշակութային հերոս

- Ժողովրդական հերոս

- Գերմանացի հերոս

- Helping behavior

- Հերոս և Լեանդր

- Սոցիալիստական աշխատանքի հերոս

- Հերոսական ֆենթեզի

- Մարտաֆիլմի կին հերոսների և չարագործների ցանկ

- Ժանրերի ցանկ

- Մեսիա

- Բարոյական աճ

- Ռանդյան հերոս

- Դժկամ հերոս

- Փրկություն

- Ռոմանտիկ հերոս

- Soter

- Տիեզերական օպերա

- Ընդհանուր բարիք

- Ողբերգության հերոս

- Յուսիա

Ծանոթագրություններ

խմբագրել- ↑ Gölz, Olmo (2019). «The Imaginary Field of the Heroic: On the Contention between Heroes, Martyrs, Victims and Villains in Collective Memory». helden. heroes. héros: 27–38. doi:10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2019/APH/04.

- ↑ 2,0 2,1 2,2 2,3 «Hero». Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Վերցված է 2015-12-06-ին.

- ↑ «Definition of HERO». Merriam Webster Online Dictionary. Վերցված է 2 October 2017-ին.

- ↑ «hero». Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ↑ ἥρως Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- ↑ R. S. P. Beekes, Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Brill, 2009, p. 526.

- ↑ 7,0 7,1 7,2 7,3 Schein, Seth (1984). The Mortal Hero: An Introduction to Homer's Iliad. University of California Press. էջ 58.

- ↑ Levin, Saul (1984). «Love and the Hero of the Iliad». Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association. 80: 43–50. doi:10.2307/283510. JSTOR 283510.

- ↑ Hyginus, Fabulae 115.

- ↑ 10,0 10,1 Homer. The Iliad. Trans. Robert Fagles (1990). NY: Penguin Books. Chapter 14

- ↑ 11,0 11,1 «Articles and musing on the concept of Fate for the ancient Greeks» (PDF). Auburn University.

- ↑ «Four Conceptions of the Heroic». www.fellowshipofreason.com. Վերցված է 2015-12-07-ին.

- ↑ 13,0 13,1 Graf, Fritz. (2006) "Hero Cult". Brills New Pauly.

- ↑ Lord Raglan. The Hero: A Study in Tradition, Myth and Drama by Lord Raglan, Dover Publications, 1936

- ↑ 15,0 15,1 Joseph Campbell in The Hero With a Thousand Faces Princeton University Press, 2004 [1949], 140, 0-691-11924-4

- ↑ Joseph Campbell. The Masks of God: Occidental Mythology Penguin, reprinted, 0-14-004306-3

- ↑ 17,0 17,1 Vladimir Propp, Morphology of the Folk Tale, 0-292-78376-0

- ↑ The Story of Simo Häyhä, the White Death of Finland - The Culture Trip

- ↑ IS: Simo Häyhän muistikirja paljastaa tarkka-ampujan huumorintajun – "Valkoinen kuolema" esittää näkemyksensä ammuttujen vihollisten lukumäärästä (in Finnish)

- ↑ [url=https://books.google.com/books?id=R948DQAAQBAJ Tapio Saarelainen: The White Sniper]

- ↑ Spencer, Herbert. The Study of Sociology Արխիվացված 2012-05-15 Wayback Machine, Appleton, 1896, p. 34.

- ↑ «The Library of Congress: Bill Summary & Status 112th Congress (2011–2012) H.R. 3001». 2012-07-26. Արխիվացված է օրիգինալից 2012-12-15-ին. Վերցված է 2013-07-28-ին.

- ↑ «Holocaust Hero Honored on Postage Stamp». United States Postal Service. 1996.

- ↑ Hook, S. 1955 [1943]. The Hero in History. A Study in Limitation and Possibility. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- ↑ Fetterley, Judith (1977). The Resisting Reader. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- ↑ Miller, Nancy K. (1980). The Heroine's Text: Readings in the French and English Novel, 1722–1782. New York: Columbia University Press.

- ↑ Grinin, Leonid 2010. The Role of an Individual in History: A Reconsideration. Social Evolution & History, Vol. 9 No. 2 (pp. 95–136) http://www.socionauki.ru/journal/articles/129622/

- ↑ Thompson. W. The Lead Economy Sequence in World Politics (From Sung China to the United States): Selected Counterfactuals. Journal of Globalization Studies. Vol. 1, num. 1. 2010. pp. 6–28 http://www.socionauki.ru/journal/articles/126971/

- ↑ 29,0 29,1 L. Sprague de Camp, Literary Swordsmen and Sorcerers: The Makers of Heroic Fantasy, p. 5 0-87054-076-9

- ↑ Northrop Frye, Anatomy of Criticism, p. 34, 0-691-01298-9

- ↑ Shmoop Editorial Team. (2008, November 11). Vanity Fair Theme of Morality and Ethics. Retrieved December 6, 2015, from http://www.shmoop.com/vanity-fair-thackeray/morality-ethics-theme.html

- ↑ Ingalls, Victoria. "Who creates warrior women? An investigation of the warrior characteristics of fictional female heroes based on the sex of the author." Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 1 (2020): 79.

- ↑ Rusch, H. (2022). «Heroic behavior: A review of the literature on high-stakes altruism in the wild». Current Opinion in Psychology. 43: 238–243. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.07.024. PMID 34454246.

- ↑ Franco, Z.; Blau, K.; Zimbardo, P. (2011). «Heroism: A conceptual analysis and differentiation between heroic action and altruism». Review of General Psychology. 5 (2): 99–113. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.366.8315. doi:10.1037/a0022672. S2CID 16085963.

- ↑ Kinsella, E.; Ritchie, T.; Igou, E. (2015). «Zeroing in on Heroes: A prototype analysis of hero features». Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 108 (1): 114–127. doi:10.1037/a0038463. hdl:10344/5515. PMID 25603370.

- ↑ Allison, S. T.; Goethals, G. R. (2011). Heroes: What They Do & Why We Need Them. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199739745.

- ↑ Allison, S. T.; Goethals, G. R. (2015). «Hero worship: The elevation of the human spirit». Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour. 46 (2): 187–210. doi:10.1111/jtsb.12094.

- ↑ Pat Barcaly. The evolution of charitable behaviour and the power of reputation. In Roberts, S. C. (2011). Roberts, S. Craig (ed.). Applied Evolutionary Psychology. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199586073.001.0001. ISBN 9780199586073.

- ↑ Hannes Rusch. High-cost altruistic helping. In Shackelford, T. K.; Weekes-Shackelford, V. A., eds. (2016). Encyclopedia of Evolutionary Psychological Science. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-16999-6_1556-1. ISBN 9783319196510.

- ↑ Chatterji, Roma (January 1986). «The Voyage of the Hero: The Self and the Other in One Narrative Tradition of Purulia». Contributions to Indian Sociology. 19 (19): 95–114. doi:10.1177/006996685019001007. S2CID 170436735.

- ↑ McDougall, Christopher (2016), Natural Born Heroes: Mastering the Lost Secrets of Strength and Endurance, Penguin, էջ 12, ISBN 978-0-307-74222-3

- ↑ McDougall, Christopher (2016), Natural Born Heroes: Mastering the Lost Secrets of Strength and Endurance, Penguin, էջ 91, ISBN 978-0-307-74222-3

Հետագա ընթերցանություն

խմբագրել- Allison, Scott (2010). Heroes: What They Do and Why We Need Them. Richmond, Virginia: Oxford University Press.

- Bell, Andrew (1859). British-Canadian Centennium, 1759–1859: General James Wolfe, His Life and Death: A Lecture Delivered in the Mechanics' Institute Hall, Montreal, on Tuesday, September 13, 1859, being the Anniversary Day of the Battle of Quebec, fought a Century before in which Britain lost a Hero and Won a Province. Quebec: J. Lovell. էջ 52.

- Blashfield, Jean (1981). Hellraisers, Heroines and Holy Women. New York: St. Martin's Press.

- Burkert, Walter (1985). «The dead, heroes and chthonic gods». Greek Religion. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- Calder, Jenni (1977). Heroes. From Byron to Guevara. London: Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 978-0-241-89536-8.

- Campbell, Joseph (1949). The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Chatterji, Roma (1986). «The Voyage of the Hero: The Self and the Other in One Narrative Tradition of Purulia». Contributions to Indian Sociology. 19: 95–114. doi:10.1177/006996685019001007. S2CID 170436735.

- Carlyle, Thomas (1840) On Heroes, Hero Worship and the Heroic in History

- Craig, David, Back Home, Life Magazine-Special Issue, Volume 8, Number 6, 85–94.

- Dundes, Alan; Otto Rank; Lord Raglan (1990). In Quest of the Hero. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Hadas, Moses; Morton Smith (1965). Heroes and Gods. Harper & Row.

- Hein, David (1993). «The Death of Heroes, the Recovery of the Heroic». Christian Century. 110: 1298–1303.

- Kerényi, Karl (1959). The Heroes of the Greeks. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Hook, Sydney (1943) The Hero in History: A Study in Limitation and Possibility

- Khan, Sharif (2004). Psychology of the Hero Soul.

- Lee, Christopher (2005). Nelson and Napoleon, The Long Haul to Trafalgar. headline books. էջ 560. ISBN 978-0-7553-1041-8.

- Lidell, Henry and Robert Scott. A Greek–English Lexicon. link

- Rohde, Erwin (1924). Psyche.

- Price, John (2014). Everyday Heroism: Victorian Constructions of the Heroic Civilian. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4411-0665-0.

- Lord Raglan (1936). The Hero: A Study in Tradition, Myth and Drama. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications. (Republished 2003)

- Smidchens, Guntis (2007). «National Heroic Narratives in the Baltics as a Source for Nonviolent Political Action». Slavic Review. 66, 3 (3): 484–508. doi:10.2307/20060298. JSTOR 20060298. S2CID 156435931.

- Svoboda, Elizabeth (2014). What Makes a Hero?: The Surprising Science of Selflessness. Current. ISBN 978-1617230134.

Արտաքին հղումներ

խմբագրել| Վիքիպահեստ նախագծում կարող եք այս նյութի վերաբերյալ հավելյալ պատկերազարդում գտնել hero կատեգորիայում։ |

- The British Hero — online exhibition from screenonline, a website of the British Film Institute, looking at British heroes of film and television.

- Listen to BBC Radio 4's In Our Time programme on Heroism

- "The Role of Heroes in Children's Lives" by Marilyn Price-Mitchell, PhD

- 10% — What Makes A Hero directed by Yoav Shamir